During the Renaissance, the government of Venice took extreme measures to maintain the city’s monopoly on supplying the finest luxury glass throughout Europe. In 1292, for example, the workers were moved to the island of Murano. To help prevent the spreading of coveted trade secrets, they were forbidden to travel abroad. In such an environment, it would be surprising to find any detailed written descriptions of glassworking processes. To my knowledge, there is only one such document from that period. It is a wonderfully precise narrative that explains how to create enameled decoration on glass vessels. This late 15th-century document is preserved in the library of S. Salvatore in Bologna, and it reports:

To paint glass, that is to say, cups or any other works in glass with smalti [enamels] of any colour you please.—Take the smalti you wish to use, and let them be soft and fusible, and pound them upon marble or porphyry in the same way that the goldsmiths do. Then wash the powder and apply it upon your glass as you please and let the colour dry thoroughly; then put the glass upon the rim of the chamber in which glasses are cooled, on the side from which the glasses are taken out cold, and gradually introduce it into the chamber towards the fire which comes out of the furnace, and take care you do not push too fast lest the heat should split it, and when you see that it is thoroughly heated, take it up with the “pontello” [punty, or pontil] and fix it to the “pontello” and put it in the mouth of the furnace, heating it and introducing it gradually. When you see that the smalti shine and that they have flowed well, take the glass out and put it [back] in the chamber to cool, and it is done.19

To see this process in action, view the latter half of the videos associated with the Enameled Goblet, Enameled Bowl, and Enameled Tazza.

This document is a genuine revelation in that it answers a fundamental technical question: How did the artisans fire high-temperature enamels (low-temperature enamels would not be invented for centuries) on glass vessels without having the vessels collapse under the force of gravity? In fact, the objects themselves reveal the answer: seven “symptoms” of the pontil-firing process have been identified.20 However, even when some or all of these symptoms are detected on an original object, they may not fully illuminate the process. The Bologna document is as detailed a period description of a complicated glassworking process as one could hope for. Would that there were more such examples!

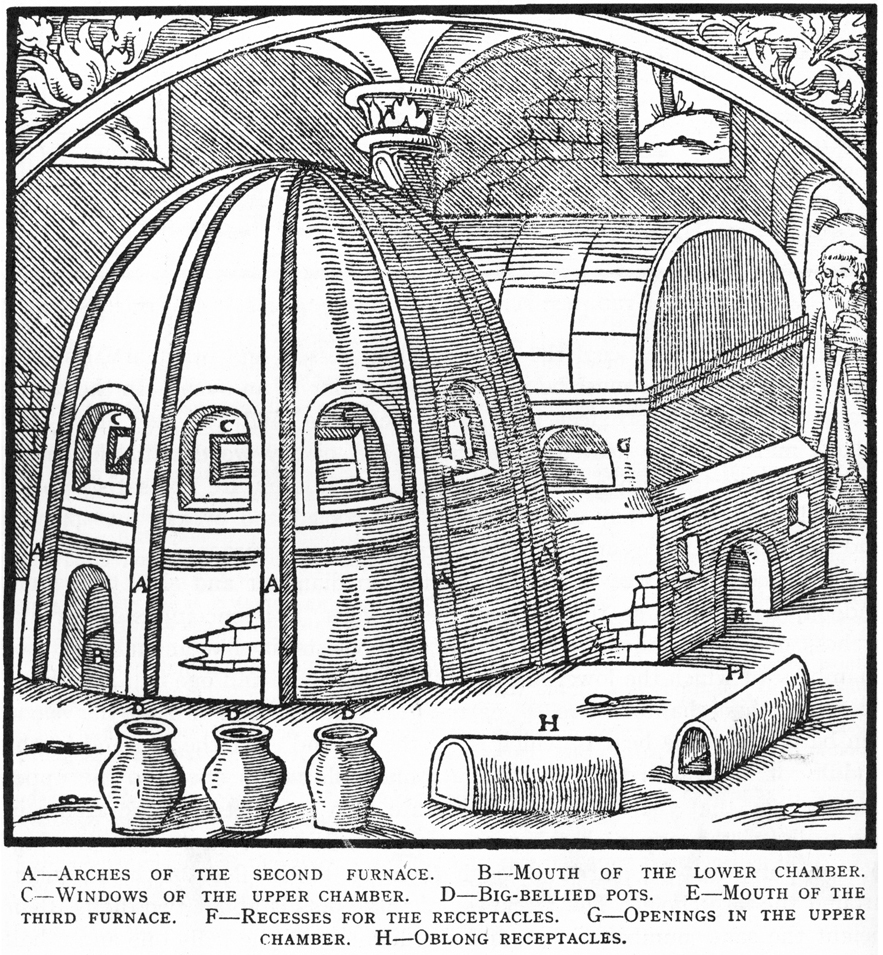

Fortunately, we have a number of illustrations of 16th-century Venetian (or Venetian-style, at least) glasshouses in operation. Most of them show the architecture of the furnace and a variety of tools, without conveying any specifics about the actual glassworking practices taking place (Figs. 37–39). However, one example is so detailed that it warrants close scrutiny and analysis.

![FIG. 37. Glass furnace, showing the upper annealing chamber. Vannoccio Biringuccio (Italian, 1480–1539). In De la pirotechnia, [Venice], 1540. Rakow Research Library, The Corning Museum of Glass (93699). Photo: The Corning Museum of Glass.](/sites/renvenetian.cmog.org/files/93699_web_edited.jpg)

![FIG. 39. Glass furnace, with workers. Georg Agricola (German, 1494–1555). In De re metallica [Berckwerck Buch, Frankfurt-am-Main, 1580, p. cccxc]. Rakow Research Library, The Corning Museum of Glass (66820). Photo: The Corning Museum of Glass.](/sites/renvenetian.cmog.org/files/Rakow_1000061004_p490_crop_RGB-apd_web.jpg)

![FIG. 42. “Glassworking at a Wood-Fired Furnace.” Denis Diderot (French, 1713–1784). In Encyclopédie [Selections], 1751–1772. Corning, New York: Corning Glass Center, n.d. Rakow Research Library, The Corning Museum of Glass (67353). Photo: The Corning Muse](/sites/renvenetian.cmog.org/files/Rakow_200003385_p005_RGB.jpg)