In the late 13th century, Venice began to produce luxury glass objects that would become popular throughout much of Europe. The group is named for one example that has been housed in The British Museum since 1876: the Aldrevandin beaker (Fig. 14). The name comes from the Latin inscription in a frieze on the object, somewhat below the rim, which reads, “Magister Aldrevandin me feci(t)” (Master Aldrevandin made it). Many other examples of these beakers have been found in widely scattered locations across Europe, even as far away as London (Fig. 15).

History of Venetian Glassblowing

The Aldrevandin Group

The Aldrevandin Beaker. Probably Venice, about 1330. H. 13 cm, D. 10.9 cm. The British Museum, London (1876,1104.3). Photo: © The Trustees of The British Museum (1876.1104.3AN32286001).

![FIG. 15. Fragment of heraldic beaker, found in goldsmith’s quarter of London at 7–10 Foster Lane. Probably Venice, about 1290–1325. H. 9.5 cm, D. 8.8 cm. Museum of London (OST82[190]<128>). Photo: © Museum of London.](/sites/renvenetian.cmog.org/files/london_000137_web.jpg)

Fragment of heraldic beaker, found in goldsmith’s quarter of London at 7–10 Foster Lane. Probably Venice, about 1290–1325. H. 9.5 cm, D. 8.8 cm. Museum of London (OST82[190]<128>). Photo: © Museum of London.

The craftsmanship of the Aldrevandin beaker and its close parallels is excellent in every way. The material itself is of exceptional clarity and colorlessness for the period. There is, at the lower edge, a foot-ring that barely reveals its starting and ending points; this can be achieved only with the greatest finesse on the part of the artisan.

Most notable, though, is the smoothness and evenness of the curving sides, together with the rather extreme thinness of the glass (less than two millimeters in most areas). This not only reveals the exceptional skill of the glassworker but also suggests the use of a special tool that was probably newly invented.

The Soffietta

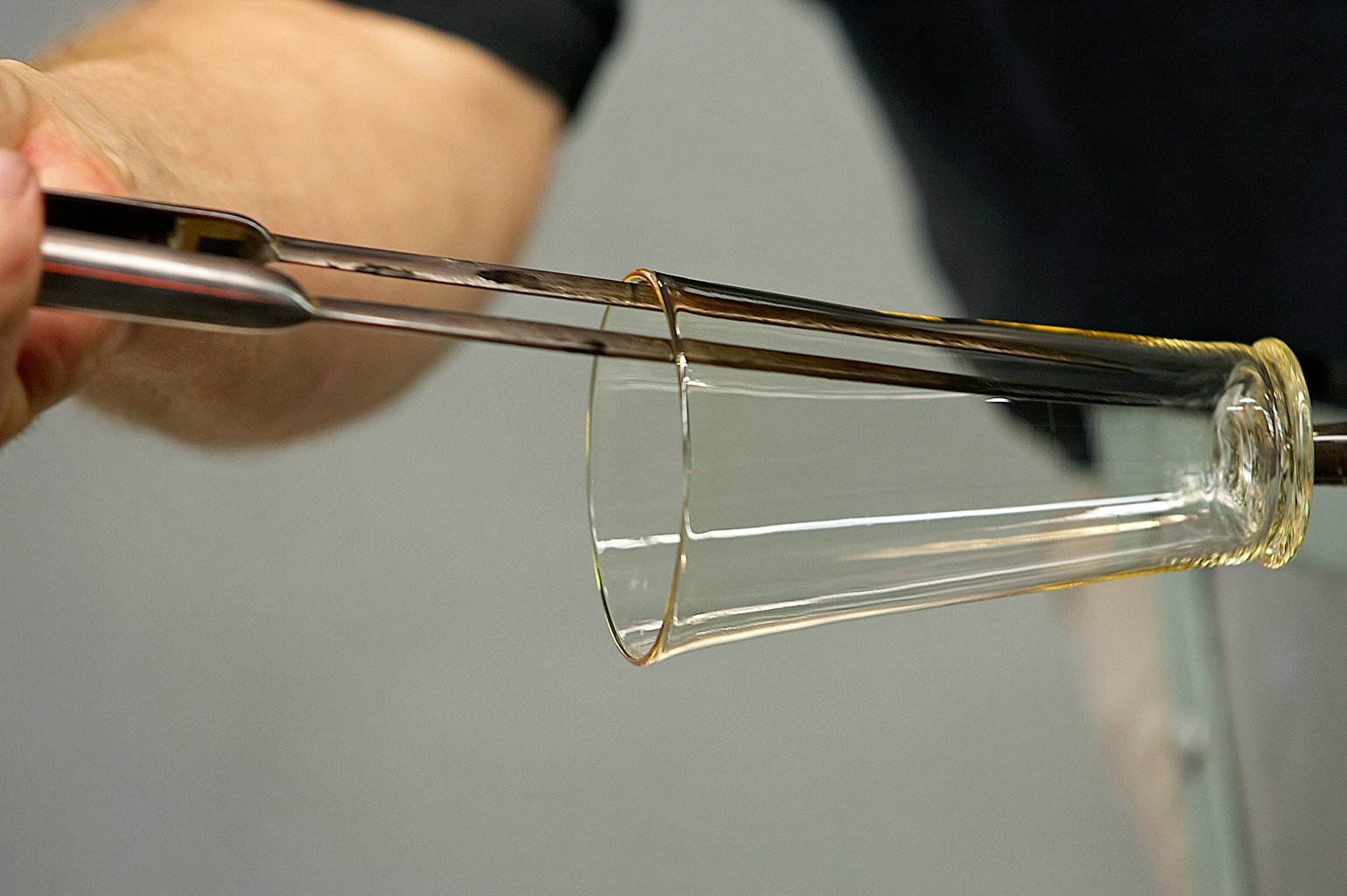

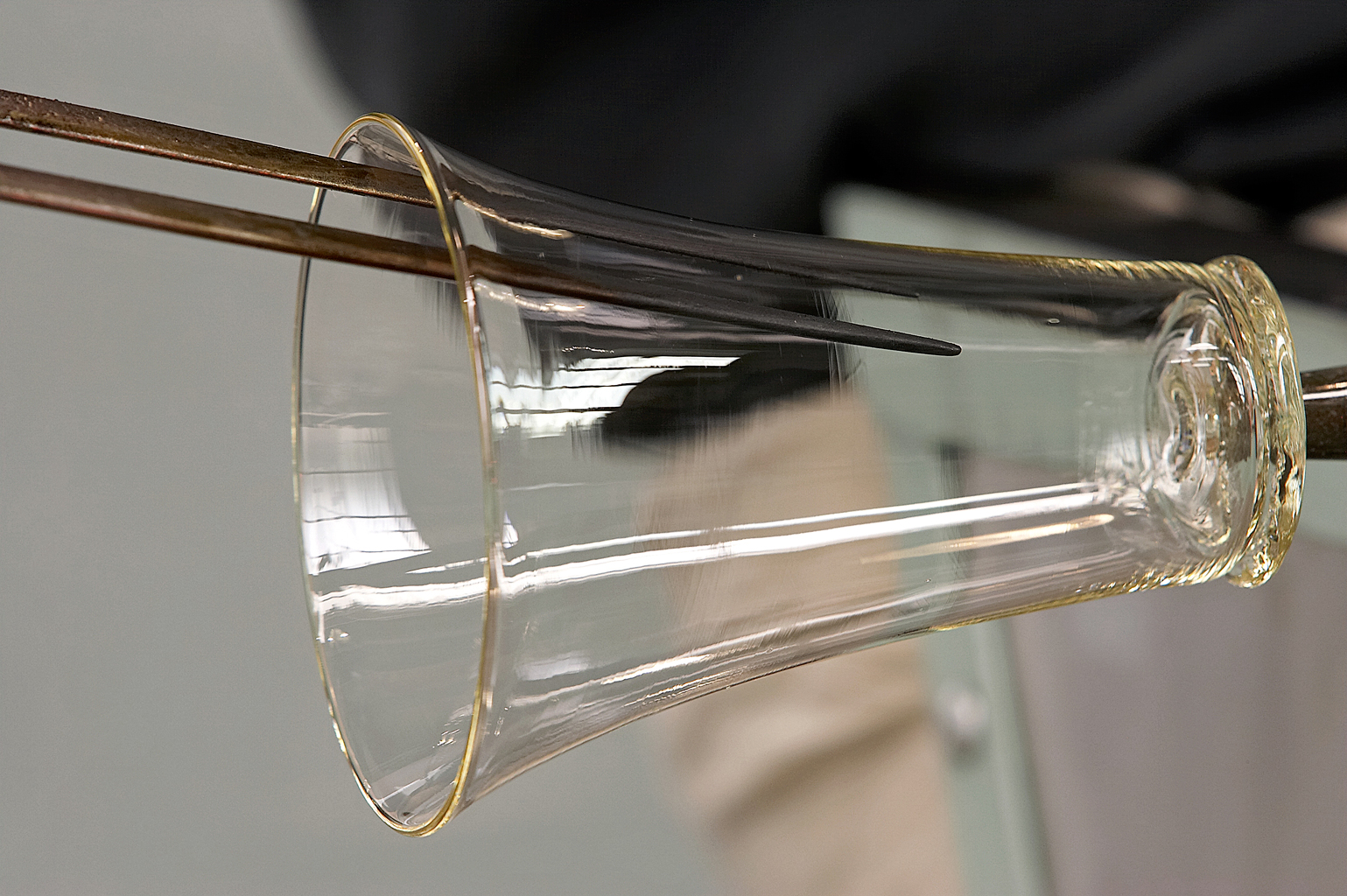

The soffietta11 is a tool that consists of a metal cone attached, at its wide end, to a tube. The tube is curved if it is employed by the blower alone and straight if the blower has an assistant (Fig. 16). The worker blows into the tube while pushing the conical part of the tool against the open end of the vessel. The conical shape allows the tool to form an airtight seal with openings of various sizes.

Three soffiettas. The two on the left were made by Carlo Dona of Murano, and the one on the right was made by William Gudenrath. Photo: Harry Seaman, The Studio of The Corning Museum of Glass.

The soffietta was a major technological advance in the history of glass, and it is arguably one of the most important glassmaking-related inventions after the blowpipe. Previously, the blowpipe had been the only tool with which the worker could inflate molten glass. This was a significant limitation because about half of the time in the glassblowing process is spent with the vessel attached to the pontil, a solid metal rod that is used as a handle. The soffietta permitted the worker to complete an object while retaining the option of inflating it further.

Before the invention of the soffietta, and even afterward in places where that tool was unknown, all of the shaping that was performed in the later stages of glassblowing had to be accomplished exclusively with hand tools (Figs. 17–21). This was apparently the case in the glass workshops of the Middle East, where objects such as the Palmer Cup12 were made. The process was very straightforward. After the lower half of the vessel was formed, the object was transferred from the blowpipe to the pontil. The upper half of the vessel was reheated and softened in the furnace, and then the jacks were employed, often forcefully, both to enlarge the opening and to expand and shape the vessel wall. Because contact with the metal tool had the added effect of cooling the glass rapidly, the work had to be performed quickly, and frequent reheating was necessary. When the object was completed, it was removed from the pontil and placed in an annealing oven to be gradually cooled.

The process of forming the upper half of a beaker like the Palmer Cup, using only jacks (shown in Figures 17–21), begins with forming the lower half of the vessel, attaching it to a pontil, and removing it from the blowpipe. Photos for Figures 17–29 are from William Gudenrath, “Glassblowing in the Middle Ages: Tradition and Innovation,” in David Whitehouse, with contributions by William Gudenrath and Karl Hans Wedepohl, Medieval Glass for Popes, Princes, and Peasants, Corning: The Corning Museum of Glass, 2010, pp. 78–82, figs. 6–18.

The upper half of the vessel is reheated and softened in the furnace.

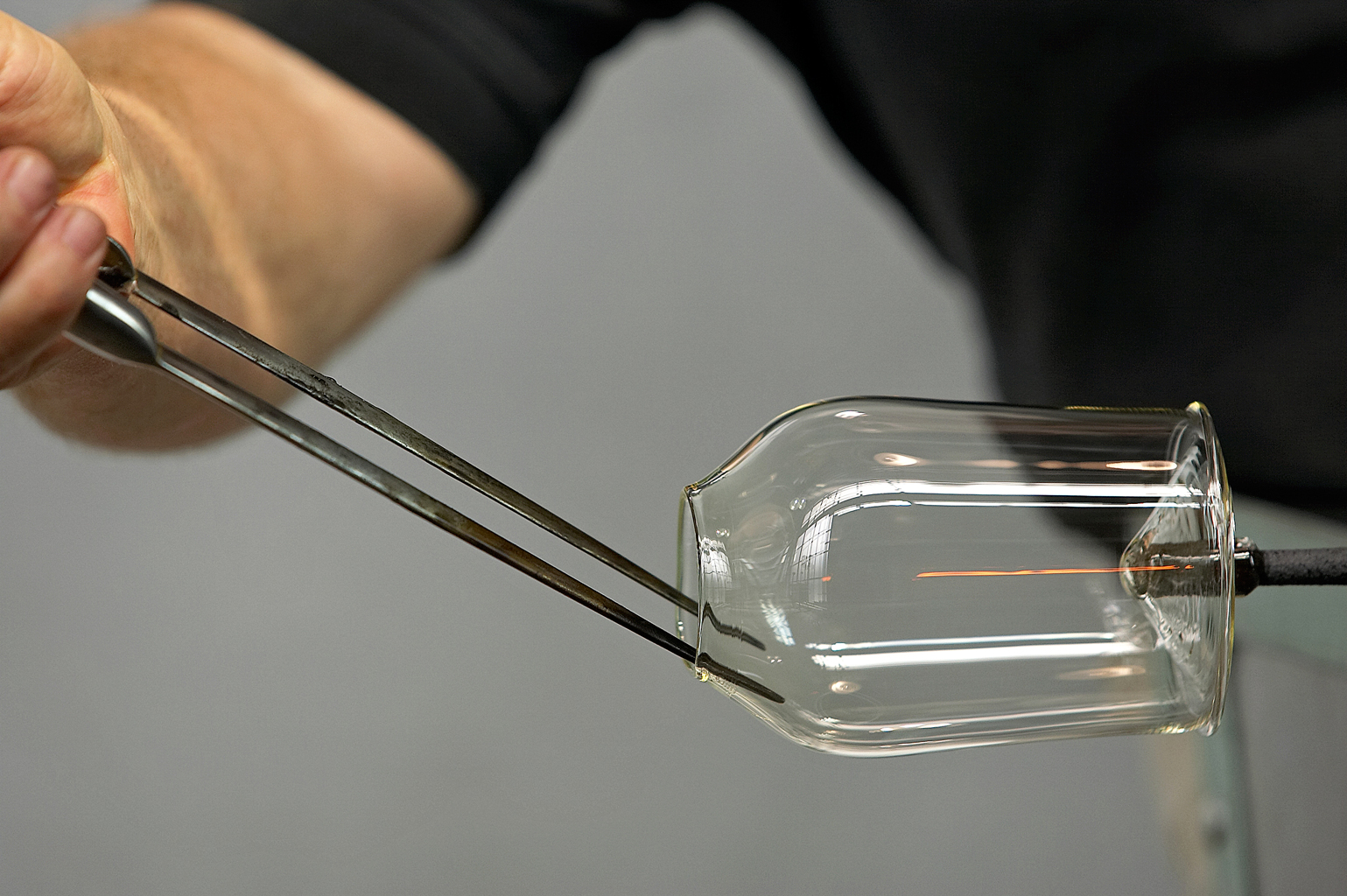

While the pontil is turned, the jacks are used to expand the sides.

After further reheating, shaping continues.

The working cycle of reheating and shaping continues until the beaker has been completed. (Tool marks left from the jacks can be seen covering the interior of the beaker.) The finished object is removed from the pontil and annealed.

Using a soffietta in addition to the jacks required more steps that had to be carried out in a specific order (Figs. 22–29). Here, the jacks were employed almost exclusively to enlarge the diameter of the opening; by contrast, the vessel wall was shaped by expansion, entirely with air pressure provided by means of the soffietta. Immediately after the jacks had been used, the glassblower held the conical part of the soffietta against the rim of the vessel while blowing, often forcefully, into the open end of the attached tube. Between reheatings, this sequence was repeated until the opening approached its final diameter. Following a last reheating, the uppermost part of the vessel was given its final shape with the jacks. The object was then annealed.

The process of forming the upper half of a beaker using both jacks and the soffietta (shown in Figures 22–29) begins with forming the lower half of a vessel like the Aldrevandin Beaker, attaching it to a pontil, and removing it from the blowpipe.

The upper third of the vessel is reheated and softened in the furnace.

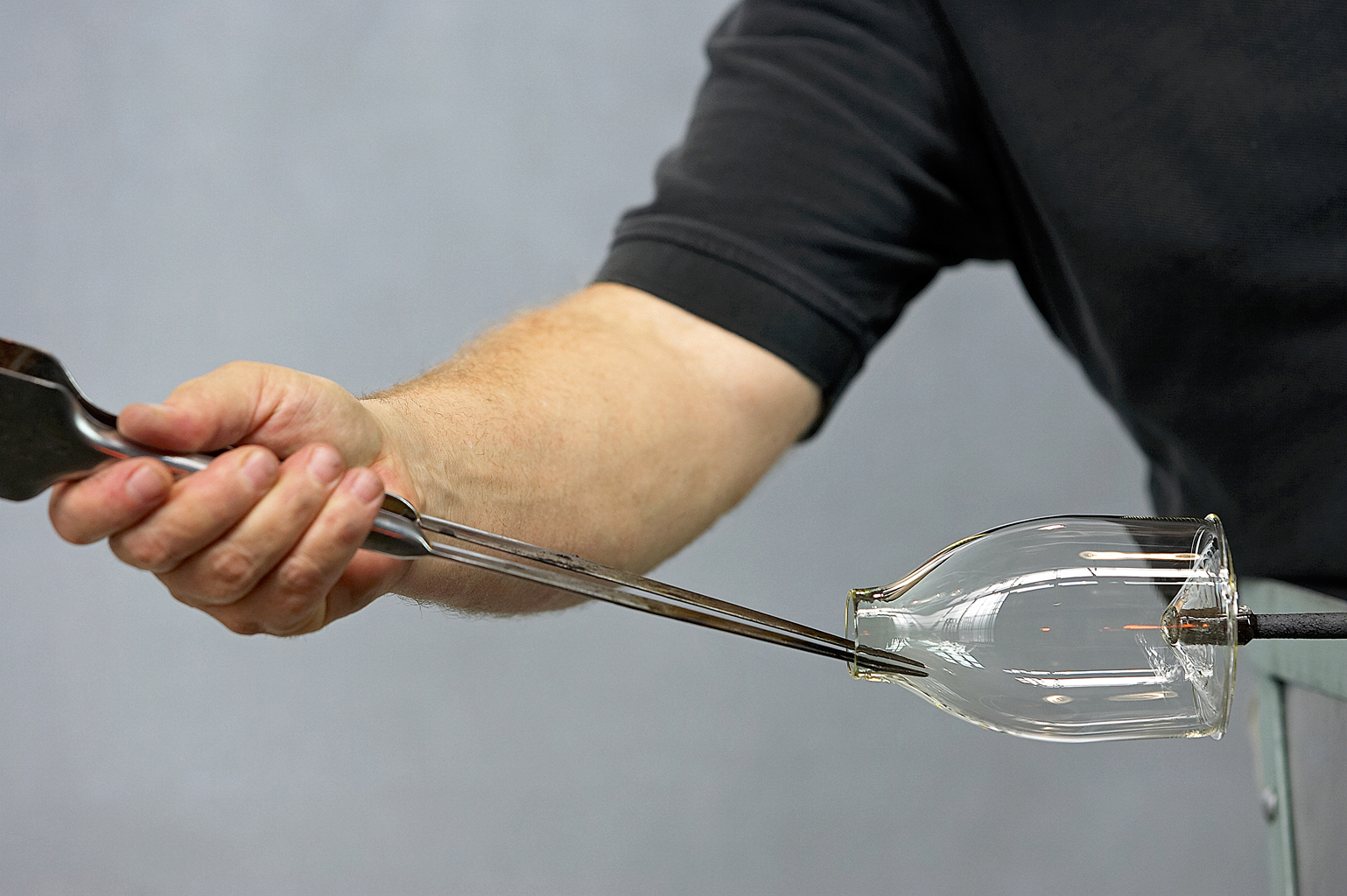

While the pontil is turned, the jacks are used to enlarge the diameter of the opening to about an inch (2.5 cm).

The upper half of the vessel is reheated.

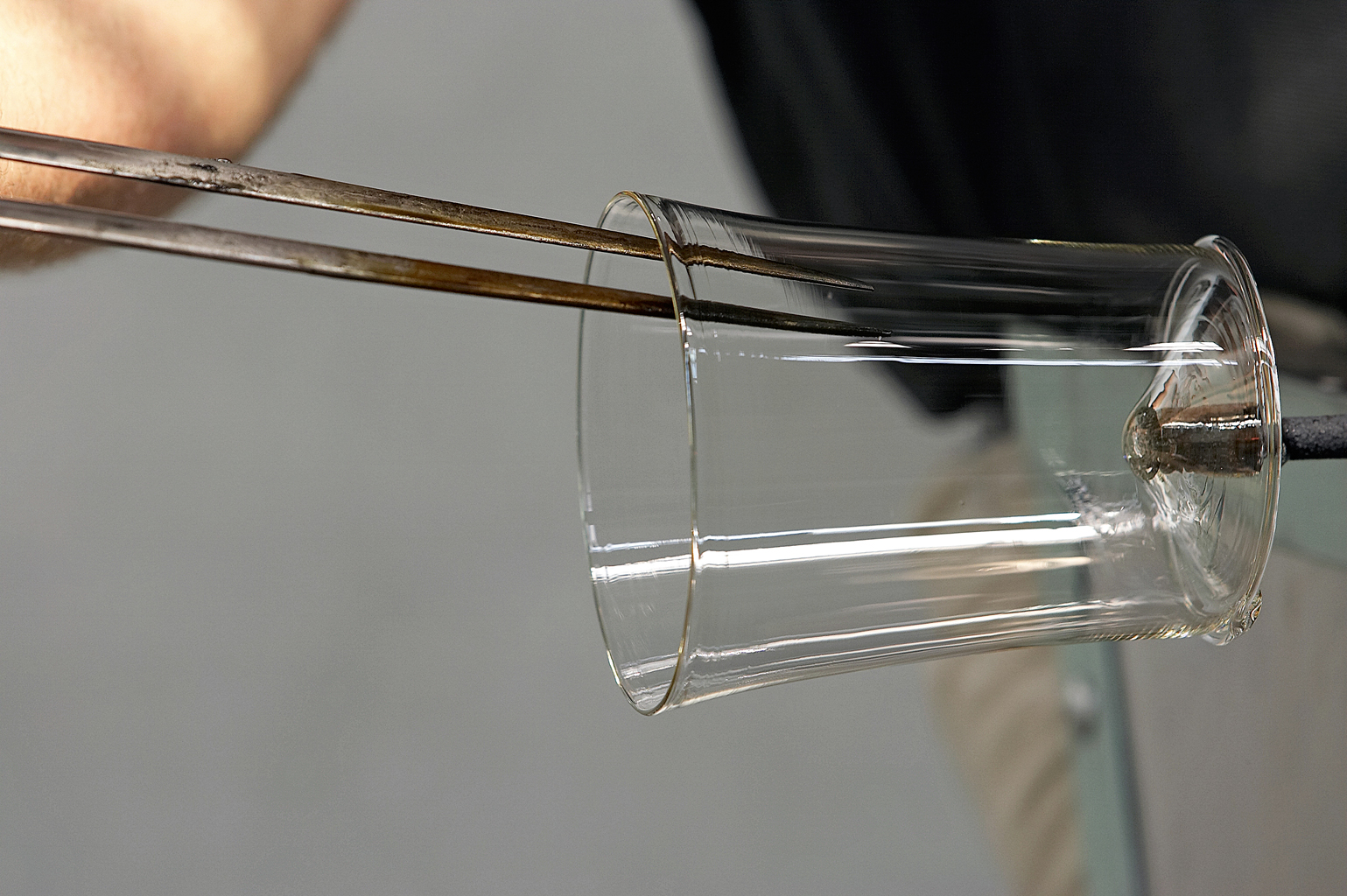

The soffietta is used to expand the softened sides by inflation.

After the upper quarter of the vessel is reheated, the opening is enlarged to a diameter of about two inches (5 cm).

While the glass is still soft, the soffietta is employed to further expand the upper quarter of the beaker. (Note that the shaping with the soffietta leaves no tool marks on the glass.)

After the upper part is reheated, the jacks are used to give the final shape to the upper eighth or so of the vessel. (Tool marks left by the jacks can be seen only in the immediate vicinity of the rim.) The finished object is removed from the pontil and annealed.

These two markedly different processes—glassblowing with and without a soffietta—leave different marks that can sometimes be detected on historical objects. A glass vessel made without a soffietta invariably has extensive tool marks both near and well below its rim. If the upper half of such a vessel was given its final form on the pontil exclusively with jacks, it will have marks on its inner surface. Glassblowing with the help of a soffietta, however, is indicated by a very different “footprint.” There are few, if any, tool marks in the areas shaped by the soffietta because only pressurized air touched the glass. A vessel whose upper half was given its final form in this manner will typically have a heavy concentration of tool marks only in the immediate vicinity of the rim.

Upon close inspection, a considerable number of tool marks can be seen on the inner surface of the entire upper half of the Palmer Cup. To a limited degree, these marks are also visible in photographs. This beaker and other objects of its type appear to have been shaped exclusively with jacks and without the use of a soffietta.

In sharp contrast, the Aldrevandin beaker reveals a very different working method: it clearly shows signs that it was manufactured with the use of a soffietta. The Aldrevandin beaker has only minimal internal tool marks, except for the uppermost inch (2.5 cm) or so. There, the tool marks are dense and closely spaced. The area below this is mostly unblemished by tool marks because this was the part of the vessel that was shaped using only the soffietta.

One of the most striking technical differences between these two groups of beakers is that most Islamic beakers have somewhat thick walls, whereas beakers of the Aldrevandin group can be made of glass blown to a paperlike thinness. Apparently, the makers’ goals were as different as their means of achieving them.

It appears that, by the early 14th century, Venetian glassworkers were already taking advantage of the soffietta. A century later, Angelo Barovier’s new cristallo, a glass resembling colorless rock crystal, became increasingly important to the growing success of the Venetian glass industry (see The Material: Making Glass in Renaissance Venice). This was due, in no small measure, to the maestro’s ability to work the glass very thinly with complete control. For the master glassblower of Renaissance Venice, the soffietta was probably an indispensable tool. Its use can be seen in all of the process videos within this publication.